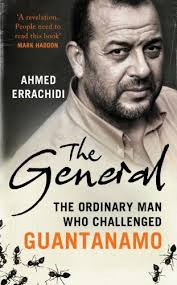

I have a problem with Ahmed Errachidi’s book, The General – and I’m willing to admit that it is a problem I might be wrong about but, for all that, it’s an issue that coloured my reading of the book.

I have a problem with Ahmed Errachidi’s book, The General – and I’m willing to admit that it is a problem I might be wrong about but, for all that, it’s an issue that coloured my reading of the book.

This is a memoir of Ahmed’s time in Guantanamo. He was picked up in Afghanistan, ostensibly for nothing, and transported – in dark agonies – to the largely lawless prison (or rather to the prison that stands outside the rule of law), where he and his fellow inmates were daily tortured, shackled for hours, tormented with sexualised imagery, force-fed or starved, blasted with music, segregated, beaten. It makes for gruesome reading but it feels tremendously important to read. This is the world in which we find ourselves. We mustn’t look away.

Ahmed is a charismatic and forceful personality. Outraged at his imprisonment for nothing, he is one of the people who is first to speak up, irrespective of the trouble it brings down on his head. This comes about in part as a result of his fluency in two languages – acting as a mediator between guards and inmates – but there is more, you sense: Ahmed is a man with a strong sense of right. He campaigns and lobbies his fellow inmates, so that their Korans are not abused by the guards, so that clocks are installed to give them a sense of time passing, so that a modicum of respect is afforded at times of prayer.

These tiny advances are, however, frequently and understandably undercut by the fact that Ahmed should not be there. But his fury never eradicates his humanity (he speaks of the occasional kindness of a guard or two, he holds his memories of his family tight, he observes nature – in the form of ants – and it reassures him abstractly, life going on in spite of unendurable horror (itself, always close at hand, hunger strikers having pipes ripped from their throats repeatedly)).

But. There’s a but. And it exists in a dubious potentially politically incorrect space where it is a question of taking a man’s word or not. A Moroccan, born in Tangier, Ahmed travelled to England as a young man and took work in hotel kitchens, plying a trade as a chef. He married, travelled between England and Tangier, working, earning a crust and doing his best for his family. So far so fair enough. Dissatisfaction – in the perfectly understandable shape of wanting to earn more for his family – and tragedy – his son Imran, was dangerously ill – combined to urge him to explore new avenues for a career and he looks into jewellery importing.

And then 9/11 occurs and he travels to Afghanistan. Why does he do this? He tells us that, watching the indiscriminate aerial bombardment, he

“became obsessed with the idea that I should help alleviate the misery of these refugees whose eyes were so full of sorrow… The conviction grew in me that if I aided these people in their time of hardship then Allah would aid me and cure Imran of an illness I couldn’t myself treat.”

There is something about this explanation that doesn’t ring entirely true. I can’t put my finger on what it is (although it is, perhaps, in part the lack of any fury: Ahmed isn’t angry, he just decides to go and help because he is a good person witnessing injustice). Now, you might say, good people do good things all the time, that’s what makes them good. It certainly makes the injustice at the heart of the book all the richer. But there is something about a proud family man who was desperately looking to resolve his family’s fortunes in order to improve his son’s health suddenly jetting off to a warzone that doesn’t ring true. We are not being told the full story here (and I sense we are not being told the full story because someone, the ghostwriter perhaps or the publisher, didn’t want to muddy the waters at all – ‘we can’t have Ahmed saying, ‘I was furious at the Americans for what the did and my sense of brotherhood compelled me’ etc).

Eventually however the daily accumulating horrors of Guantanamo erode your sense of ellipsis. No-one, not the world’s worst terrorist, deserves what happens in Guantanamo. The fact that the daily horrors eventually overwhelm you is power enough to recommend the book, even in the face of niggles.

Any Cop?: If you are interested in the state of the world, if you feel like understanding the mistakes of the past might help us not to make those mistakes again in the future, you should read The General.