A woman wakes in a room. A lightbulb swings overhead. There is a man with a knife. A perfectly nightmarish opening you might think. The blade plunges into her side, once, twice,

A woman wakes in a room. A lightbulb swings overhead. There is a man with a knife. A perfectly nightmarish opening you might think. The blade plunges into her side, once, twice,

“As the blood fell out of me it took my eyes and ears with it, so that I couldn’t feel the room around me anymore, couldn’t feel the swinging light bulb, the insects swarming through the walls, the man standing in his worn boots. Everything was vanishing around me…”

She dies but when she finished dying “she came back” and then “moved unsteadily to the door”. Outside the room there is a dimly lit stairwell. She can hear “murmurs coming from deep within the house, its whispered language, resonating from a secret unreachable place in between the stone walls”. The house belongs to that of her killer. There are photographs on the wall of him, looking different to how he looked previously, when he killed her, with his daughter.

She leaves the house, walks the streets in the dark, the streetlights casting “dim egg-shaped circles of light against the dark concrete and asphalt”. “Over and over I penetrated the egg of light,” she tells us. She goes back home and her landlady chatters on about how unsafe the city is. Our narrator informs us:

“I had nothing to give her, would never have anything to give someone who wanted to know what had happened to me, what was happening to me. They should know not to ask a question that couldn’t be answered.”

In her room, she takes a bath. A creature wriggles “serpentine” out of the faucet, looking “like a braid of twisted hair, a gelatinous clump, thick and singular”, filling the bath alongside her.

“Then it zipped quickly under the water and pushed inside me, all of it in an instant rushing into me, filling me up.”

She gets up, gets dry and goes out to a bar where she becomes aware of a person looking at her,

“…but I was not the deer in the centre of the road, they were not the car speeding rashly toward me. They were like a cat balanced on a fence, looking at me through a window, motionless and calm as their eyes dilated larger and larger, paws delicate on the tops of the posts.”

This person gives our narrator a gun before disappearing. She looks around the bar for them but finds instead a couple who invite her to join them, buy her a drink, console her when she is upset. They take her back to their place, take drugs together (after which our narrator watches a streak travel down a wall and listens to a knocking sound which becomes a part of her, a child) and then our narrator passes her blessing down upon them and shoots them both dead.

She leaves the couple, walks the streets, sees her killer with his daughter, gets close enough to touch but doesn’t touch. “A car ripped through the intersection… nearly scraping [her].” She gets inside and is taken to a multi-storey car park where she is faced again by the women she recently shot (“her incomprehensible eyes facing mine”). Our narrator vomits up an eel. As the thing lies “motionless and banal” between them, the recently shot woman says the word “Burning”. And then:

“She shook her head again as though she didn’t understand, and I didn’t understand either,”

As flames move from the woman’s hands and up her arms until they consume her and “there was nothing left there, there was no name for that could be used for what was lying there pathetically on the floor; I didn’t have a name for it.”

The car waits for her outside. She gets back in and is driven through the city until she arrives at a gas station where she covers herself in petrol (I think), petrol being the decayed form of creatures who are millennia old, who commune with the child inside her. The gas station attendant comes out and looks at her and then goes back into the gas station and she follows him. He lies down on the floor. They commune, in a way:

“I needed to pull him to the surface, toward me. I needed to open the door at the front of his eyes and lower myself into them so that I could reach that place behind his eyes where he lurked and touch him, and feel him not just in my fingers but deeper inside me; feel him inside the place behind my own eyes as well.”

“The child was in a frenzy, throwing itself around with a violence inside me, making me wince with pain, it was crying out so loudly it made my head ring and spin. A fever struck me suddenly like a bolt of electricity from heaven, terrible and hot and nauseating but strangely uplifting, an invigorating agony that settled over my shoulders and then wrapped itself around me…”

There is a kind of religious ecstasy that follows. After which, the attendant is sort of frozen in place,

“prostrating himself devoutly to the ground that prevents our endlessly falling-through the black infinity of nothingness, the ground without which our grotesque bodies would simply fall and fall and fall, would ragdoll through an endless nowhere so purely nowhere it doesn’t have any there within it, doesn’t have even a hint of a possibility of there, so absolutely nowhere that if we fell through it language itself would plummet alongside our bodies, meaning would fall apart and disintegrate under the expansive emptiness of that not-place, flesh and speech becoming equally as twisted and futile, blown apart by that empty space.”

Our narrator latches on to a kind of song, a duet, borne of “the buzzing that lurks in the walls”.

She leaves the gas station, is struck by the sun overhead and the insect-like cars speeding by her. There is a house in a field full of “yellow-brown stalks”. She wades through the stalks, makes her way up the steps into the house cutting her leg when one of the wooden porch stair s breaks.

“Pain shimmied up my leg electrically before settling into a red pulsing concentrated in my ankle and foot.”

Inside the house is a woman in a chair who gets up and makes her way towards the narrator only to return to where she is sitting every time our narrator blinks. The woman in the chair may also be our narrator.

“The endless loop, the redirection, the entrapment: this was a scene I had seen before, in a movie, on a stage, in a memory, no – somewhere deeper, hidden beyond the cobwebs of my twisted recollections, in a place deep inside me, I could almost see it.”

There is also a cloudy mirror that disturbs the child inside her and so she flees both the mirror and the endlessly repeating woman. She hurts her ankle as she runs and ends up crawling back to the road where the car and the driver are waiting for her. The driver takes her to hospital with endlessly white floors and white walls. She gets into bed and

“then I truly fell backward, fell backward into the space that exists in between everything, into the dream of the will that upholds the boundaries of all things, the dream of the will which articulates the separateness of all things.”

There then follows an interlude in the white room. She sees a muttering man sitting cross-legged on the floor across from her. On the left side of the man’s chest is a slit from which “a black, thick substance [is] flowing evenly and unendingly down into his lap, splashing on to the floor and moving across it like a stream.” She follows the stream until it leads her to a hole, “perfectly round like an ice-fishing hole.” She peeks through the hole, which is “brighter than the glow of the white room”. On the other side of the hole, the sun is shining, and there is vegetation and a horse. The dark substance flows out through the hole, down the wall and across the landscape “where it gurgled in the weeds”.

Back in the room, the child appears behind the man. The two of them look at her “with the same incomprehensible vacant expression”. The man touches the child and the child’s chest opens and a second stream joins the first. Next, she’s leaving the room, talking to a woman in the hallway (“I opened my mouth and tried to push my questions out but she interrupted me before I could, her speech all rushing quickly like a rapid river, frothing and chaotic, her words stumbling and falling over each other in their race to exit her mouth, trampling over each other like they were escaping a burning theatre”) who eventually speaks well of the narrator’s child before rushing off. After which our narrator is taken in a car to the same field where the horse lives and finally, finally, she “understood, and knew what (she) had to do next.”

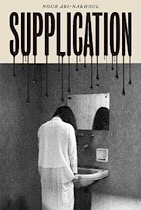

Now, it’s fair to say that I didn’t get along with Supplication at all. When I was younger, this would lead to a bad review. But I understand how much work goes into a book and how it takes a village etc so what I’ve tried to do above, via what is essentially a lengthy synopsis, is give you an idea of the book that includes as much of Nour Abi-Nakhoul’s writing as seemed sensible. If you are enticed by the fever dream narrative or the (what is for me, frankly overwrought and hyperbolic) writing style and it appeals to you, then by all means treat yourself to Supplication with our blessing.

Any Cop?: Using the words littering the cover of the book: a “philosophical exploration of identity”, “a hallucinatory literary horror”, “an actual nightmare”. All these things are true in their own way.